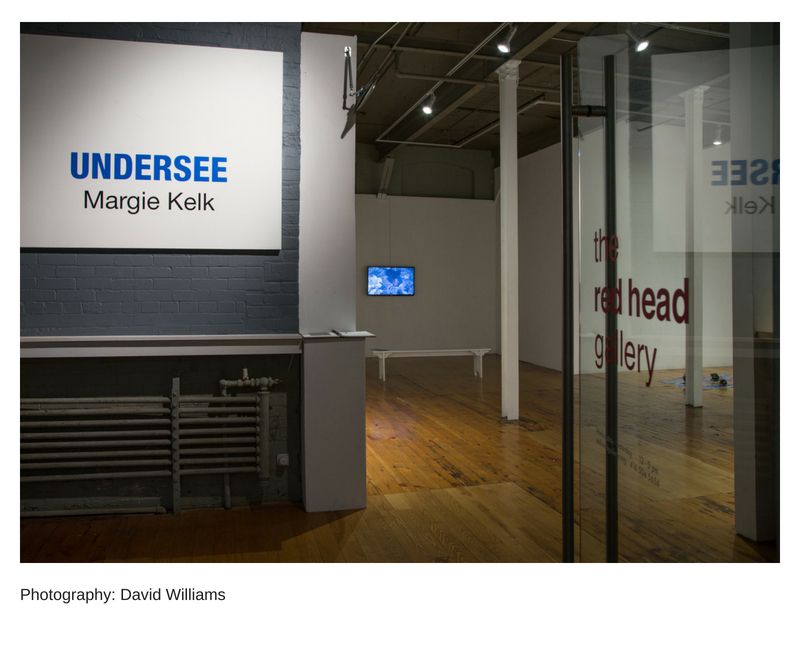

UnderSee – The Red Head Gallery, August 29 - September 22, 2018

Last winter, I was fortunate to be able to travel to Antarctica, and I was deeply moved by what I saw there. Human activity is governed by strong restrictions ratified by nations that have agreed not to claim any part of the continent for themselves; therefore the land and its inhabitants (seals, birds, whales and fish) are for the most part protected from direct human interference. Seals and penguins show no fear of humans; it is amazing to see just how interested baby seals are to get a closer look at people.

Antarctica is beautiful, with magnificent icebergs and glaciers glinting blue in the sunlight. But this beauty has become threatened indirectly by human activity. Greenhouse gasses and climate change are produced by modern civilization. The seas are growing warmer, and this will cause a great loss in biodiversity in once cold Antarctic waters as plants and animals are unable to adapt to warmer temperatures and die off. High levels of ocean acidification caused by the absorption of high levels of CO2 will cause more ecological havoc, as marine invertebrates and corals are adversely affected. This will alter key Antarctic marine food chains, and, unfortunately for humans, cause flooding in many parts of the world as the Antarctic ice shelf melts away and releases more and more water into the oceans. All of this creates a very depressing picture.

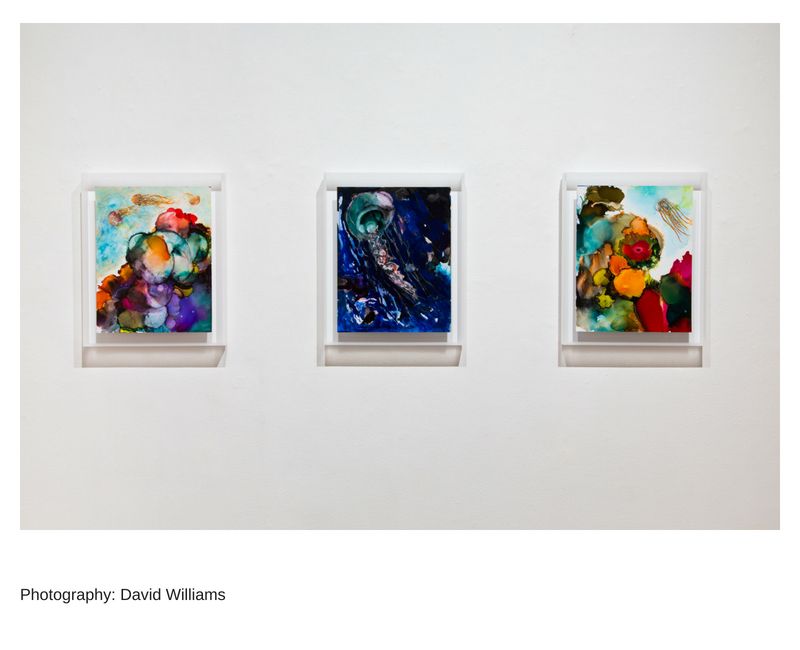

The very existence of Antarctica is now threatened by human activity. I am returning this winter for a second glimpse of the frozen continent, which I passionately hope can be preserved. I am producing drawings inspired by the beauty of Antarctic sea life. I have worked with animator Lynne Slater to finish a stop-motion film which revolves around the destruction produced by human pollution in the marine environment. Antarctica is now the focus of my creative output as I work to show my audience what a beautiful continent we risk losing.

- Margie Kelk

Undersee: Margie Kelk

We might very well “undersell.” If we’re unkind (or, in an acutely narrower sense, if we’re in the military), we might “undermine” someone or something. At some point we will all “underline,” and we will most certainly “undergo.”

But we won’t (or don’t) “undersee,” at least not according to my Shorter Oxford Dictionary. The closest to that would be to “overlook” (though there is, of course, “oversee,” typically used, however, in a much different way), which tells us something about our egos (clearly we’d prefer to be over than under). The odd and uncomfortable inversion of things suggests we’ve a mastery of things, but merely neglected or forgotten something fortuitous, and, oh well, proceed onward in our blissful ignorance. To admit we might “undersee” would imply a shortness on our part, a lack, and we can’t have that, can we?

In his book In The Blink of an Eye, zoologist Andrew Parker argued that it was the development of vision, of the organ that is the eye, that caused the Cambrian Explosion, the massive expansion of phyla – an important level of classification of animals – that occurred in a remarkably brief geological time period of 5 million years. Underseeing, in this context, would be a costly error leading to the demise of individuals and perhaps entire species, falling prey to more “insightful” animals. To see, to see fully, was a matter of life or death.

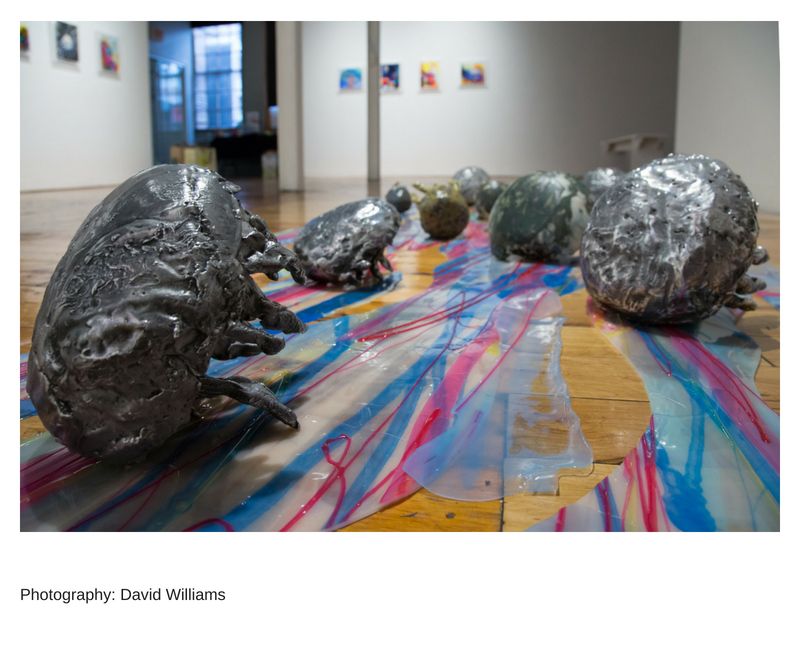

That’s at the heart of Margie Kelk’s Undersee, sculpture, drawing, and an animated video work that uses the word-play around “undersea” (because that is what this exhibition of sculpture, drawing, and animated video aesthetically iterates) to speak to the issue of seeing as a means of participation and bearing witness in and to our world – in short, to the very real, very pressing, issues of life and death on the multiple levels of the individual, the species, and our host planet.

In the animated world (a piece done in collaboration with Lynne Slater and with music composed by Alan Sondheim), we are visually given a world of seeing and being seen. A large, grouper-like fish cruises in and out of scenes, bearing witness to the world as it plays out here, undersea. What appear like disembodied eyes scoot around on sand and rock, keeping a literal and metaphoric eye on things ecological even as transgression and intrusion occurs in the guise of what seems to be an oil spill, occluding the world yet not utterly overwhelming it, and even cleared away – healed – by its very creatura.

There is no “underseeing” going on here, no “overlooking” either. Form and function coalesce. Nature knows how to fill in the blanks, niches are filled, and an ecosystem becomes a holistic entity. It’s the intrusion of humankind’s workings and messes that upsets the proverbial applecart, but here in Kelk’s envisaging, the centre still holds, the mess is cleared away – if only temporarily – and even an old shipwreck is co-opted by Nature, become an interwoven part of the fabric of things. It’s seeing that did this, the evolution of predator/prey relationships, the development and use of camouflage, the development and use of new defensive strategies – all shaping the weave of the world. The late philosopher Gregory Bateson wrote extensively about the primary importance of “the pattern which connects,” about relationship as absolutely fundamental to the structure of the world. Margie Kelk’s Undersee addresses and aesthetically explores that issue directly

Yet it is our (human) underseeing that could be the undoing of it all, our (human) resistance in comprehending the weave of the world as anything else but a resource, as something to exploit to the edge of extinction. The 17th century saw its own cultural version of the Cambrian Explosion with the development of optics – the microscope to see into the minute, the telescope to see into the macroscopic universe – and ignite what we ended up calling the Scientific Revolution. We saw that permatozoa had tails, that Jupiter was orbited by moons, but in a very real sense ultimately chose to glean from it all nothing beyond how to better extract wealth from a priceless world. This was underseeing, of an intentional sort, driven by motivations of an entirely human sort entirely foreign (and of course wildly dangerous and phenomenally destructive) to the self-regulating ecosphere. The very first sentence in critic, writer, and artist John Berger’s introduction to his hugely influential book Ways of Seeing reads “[t]he relationship between what we see and what we know is never settled.” And while we are still able to witness (for the time being, anyway) the miracle that is a jellyfish – which Kelk aesthetically reinvests via painting and sculpture – are we seeing it, or are we seeing fragments of a being? Do we see to know? To really know?

The most famous of the Apostle Paul’s writing, the moving and wildly misunderstood Chapter 13 of the Letter to the Corinthians, suggests that “[n]ow we see only reflections in a mirror, mere riddles, but then we shall be seeing face to face.”

Well, he was at least partially right; we’ve proven time and again that we do see only reflections in a mirror. When we look at the world, we really see only ourselves.

And that’s what it is to truly undersee.

Gil McElroy

July 2018