Carnegie Gallery, Dundas, Ontario, 2009; Gallery Gora, Montreal, Quebec, 2008; Propeller Centre for the Visual Arts, Toronto, Ontario, 2008

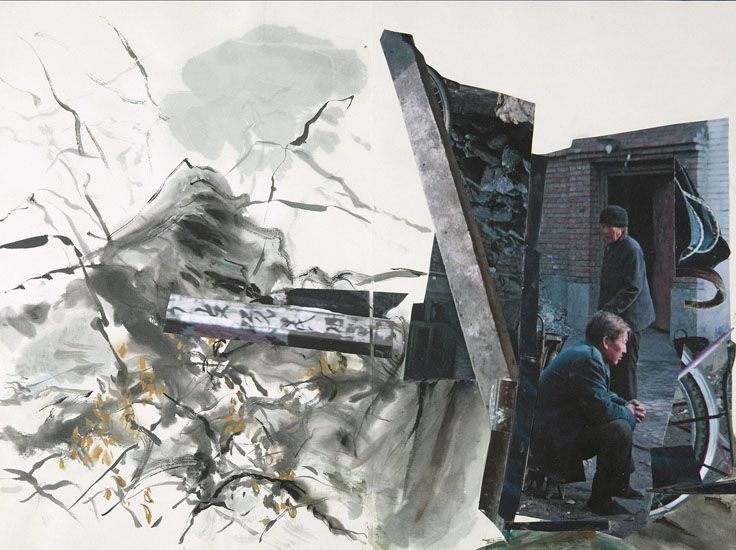

A friend and I went to Datong, China, a city west of Beijing, in the middle of a very poor coal-mining region. There, we visited sites of exceptional ancient craftsmanship and beauty, the Yungang Caves, filled with Buddhist carvings, and the Hanging Monastery, a centuries’ old building attached by poles high up against the walls of a cliff. These were impressive, but what impressed me the most about the region was the poor quality of life endured by the people of Datong.

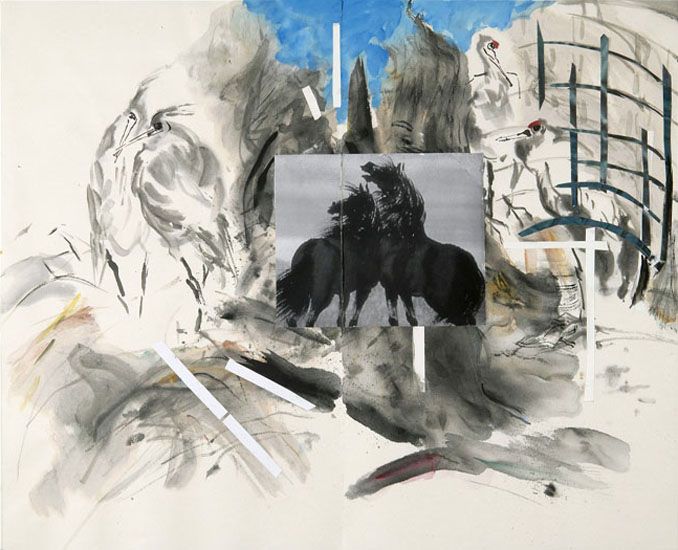

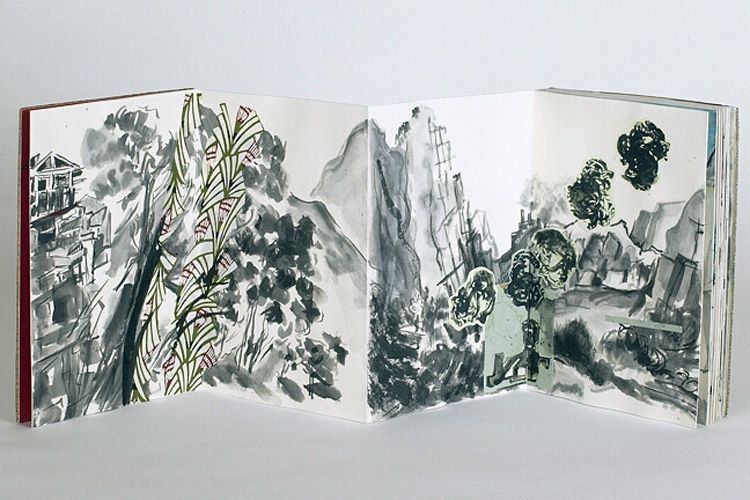

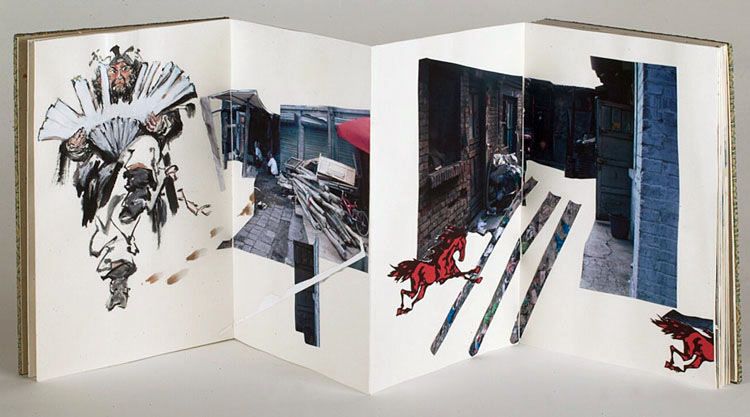

The town was drab. Lumps of coal lined the streets, and piles of coal stood at the doorways of homes, ready to be used as fuel for heating or cooking. The acrid smell of coal dust was everywhere. The inhabitants of the town looked weathered and depressed. This sad reality created quite a contrast to the graceful flowers and singing birds to be found in so much traditional Chinese art and handiwork, examples of which had been for sale at the various tourist sites I had visited. The Datong book was a way in which I could record the mixed impressions I received while walking the streets of this gray town. I produced another book, The Paradox of China, after visiting Inner Mongolia a year later. This book echoes many of the same themes I found in Datong.

A third book, Caged, centers on the Chinese love of caged birds and goes on to show members of the Chinese populace themselves, like birds, imprisoned in poverty and poor living conditions. (The bird-flu scare happened to break out while I was juxtaposing photographs of chickens with women whose job was to watch over them.) The drab life of the poor, who are a significant percentage of the population of China, stands in great contrast to the colour and wealth of cities like Shanghai and Beijing, cities visited by Western tourists who only see urban industry and development.

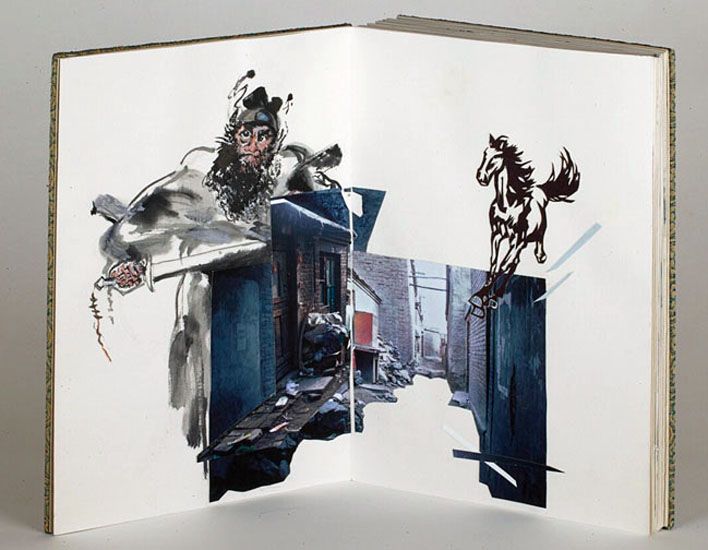

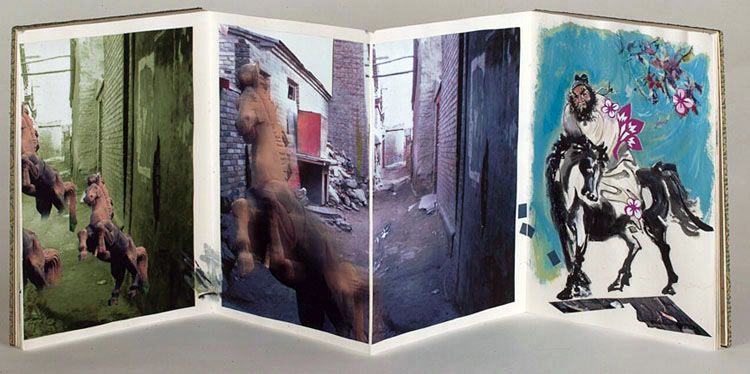

Another book, Zhong Kui, is a fantasy based on a legendary Chinese general who worked to rid the Chinese people of malicious spirits threatening their homes. I have turned Zhong Kui into a sort of modern-day Robin Hood who brings beauty and prosperity into the sordid lives of the urban poor as he strews flowers on gray streets lined with dilapidated buildings. One might say he represents social reform in a China which has no time to deal with the social immobility of lives oppressed by drudgery and despair.

China is no longer an isolated country. The pollution produced by Chinese factories now reaches as far as Korea, Japan, other parts of Southeast Asia, and Russia. It is important to recognize China’s environmental and social problems in light of the conservation and human rights issues affecting so many of us in today’s world.